This blog has also been published by the JUSTICE GAP here

Excerpts were quoted in a Law Society Gazette article here: https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/law/defendant-nationality-declarations-offensive/5063715.article (see also the lively comments thread)

A new requirement is in force (with effect from Monday 13th November) that requires every defendant appearing before a Criminal Court to confirm their nationality, or risk a prosecution and imprisonment.

The provisions are as follows:-

Section 162 of the Policing and Crime Act 2017 provides as follows:

162. Requirement to give information in criminal proceedings

In the Courts Act 2003, after section 86 (alteration of place fixed for Crown Court trial) insert—

86A Requirement to give information in criminal proceedings

(1) A person who is a defendant in proceedings in a criminal court must provide his or her name, date of birth and nationality if required to do so at any stage of proceedings by the court.

(2) Criminal Procedure Rules must specify the stages of proceedings at which requirements are to be imposed by virtue of subsection (1) (and may specify other stages of proceedings when such requirements may be imposed).

(3) A person commits an offence if, without reasonable excuse, the person fails to comply with a requirement imposed by virtue of subsection (1), whether by providing false or incomplete information or by providing no information.

(4) Information provided by a person in response to a requirement imposed by virtue of subsection (1) is not admissible in evidence in criminal proceedings against that person other than proceedings for an offence under this section.

(5) A person guilty of an offence under subsection (3) is liable on summary conviction to either or both of the following—

(a) imprisonment for a term not exceeding 51 weeks (or 6 months if the offence was committed before the commencement of section 281(5) of the Criminal Justice Act 2003), or

(b) a fine.

(6) The criminal court before which a person is required to provide his or her name, date of birth and nationality may deal with any suspected offence under subsection (3) at the same time as dealing with the offence for which the person was already before the court.

(7) In this section a “criminal court” is, when dealing with any criminal cause or matter—

(a) the Crown Court;

(b) a magistrates’ court.”

The provision is offensive and objectionable, and introduced without justification or consultation. Why nationality? Why not require confirmation of ethnicity or of religion? Perhaps instead of requiring a question and answer routine, the Court could just write down the defendant’s skin colour.

It is presumed by some the legislation is to assist with the speedy deportation of “foreign” criminals. But how to monitor them once identified? Well lock them up obviously – something that is 9 times more likely to happen if the foreign national is non-white, as evidenced in the Lammy report.

But after that? It is a only a short step from obtaining verification of nationality to requiring the foreign defendant to be tagged , a digital equivalent of being forced to display a star or triangle.

Enforcement

How are the provisions to be policed? If a defendant fails to answer, it presumably falls on the Prosecutor to lay a charge, yet the CPS have had no training or guidance in respect of this legislation.

How will the charge be proved? The prosecutor presumably cannot be a witness in their own case. Will the Judge be required to give evidence, or treat it as they would a contempt? (See para 6 above) Is the defence Advocate professionally embarrassed in the substantive proceedings as well as the nationality offence?

There may well be a temptation for a foreign national appearing in Court to keep their head down and answer “British”, to avoid some unspecified future sanction.

But perversely, as a British born citizen ashamed of this legislation and outraged at it’s purpose, the temptation for me were I appearing as a defendant would be to refuse to answer out of sheer bloody-mindedness (“don’t tell em Pike!”) or to say something flippant (European? Independent republic of ISLINGTON?) That is probably the British in me coming out.

Answering questions in these circumstances (rather than sticking up two fingers) would feel “un-British” – as alien as compulsory ID cards.

Absurdities

Is it permissible to answer “none” if the defendant is stateless, the refugee without a Nation home?

What of the defendant who answers one nationality, but is believed to be of another (the first limb of the s3 offence?) How is the “true” nationality to be proven?

Is there a defence if the defendant genuinely believes they have acquired British nationality and answers accordingly but in fact has a status still undetermined, or is it a strict liability offence?

What is the penalty for the prankster who answers “Vulcan” or “Jedi”?

Do they get a second chance, or like the drink-driver at the police station who doesn’t blow into the tube hard enough, is it a one-off opportunity?

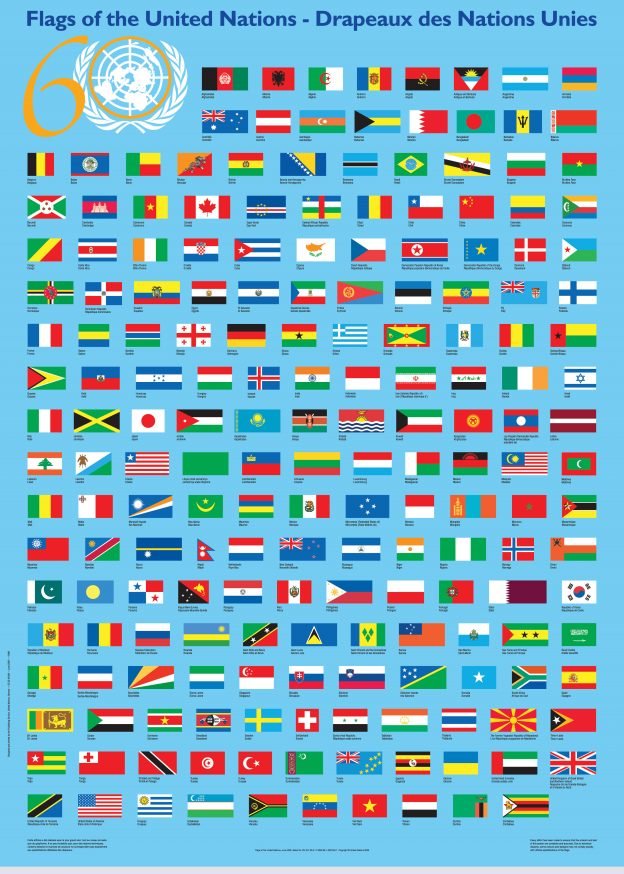

Which nationalities are recognised? The 193 currently recognised by the UN, or a broader definition? There are said to be 270 nationalities (and 300 different languages) in London alone.

What of dependent territories, or those are on the verge of becoming sovereign nations? What of autonomous regions of different nations? Can a resident from Barcelona answer “Catalan”?

Are fat-cat tax avoiders to say “British”, or name their off-shore domiciled Nationality?

What of those with joint or dual nationality- do they get to choose?

How about somebody with mental health issues who is unfit to plead-are they also unfit to confirm Nationality?

What about a defendant who is silent throughout the proceedings? Mute by malice, or by visitation of God?

Conclusion

At this post-Brexit time of national discourse leading to discontent, with the issues of prejudice and discrimination in the criminal justice system to the fore after publication of David Lammy’s report, the timing of this rushed and ill-judged legislation is unfortunate.