Jack Leslie: the full story–guest blog by Bill Hern

Introduction:- Jack Leslie was a footballer of exceptional talent who played for Plymouth Argyle in the 1920-1930s, and was selected for England in 1925 but denied his place because he was black. In 2020 two Argyle fans launched the JACK LESLIE CAMPAIGN, and authors Bill HERN and David Gleave published FOOTBALL’S BLACK PIONEERS. Jack Leslie features as a chapter in that excellent book, and Bill wrote a longer version of Jack’s story for the Campaign website here. Jack’s story is not just a football story- it is a history story, a family story, and a civil rights story. The full story is published here, as a guest blog by Bill Hern (who retains copyright-see notes below)

The Jack Leslie story – by Bill Hern

“If you’ve heard of Plymouth Argyle’s first black player, John (known as Jack) Francis Leslie, it is almost certainly because you are either an Argyle fanatic or possibly vaguely recall Jack as the man who was selected for England in 1925 but then ‘dropped’ when it was discovered he was black.”

That was the opening paragraph when I first began writing about Jack Leslie in Autumn 2017. Within three years, thanks almost solely to the efforts of the Jack Leslie Campaign, Jack is now the best known black footballer in Britain. He is about to have a square in Plymouth named in his honour and a statue erected outside Plymouth’s ground, Home Park.

No longer a hero only in the eyes of Plymouth supporters with a keen and proud sense of history, Jack is now a public figure.

His place in history is cemented not by the loyal service he gave to Plymouth,playing 400 games and scoring 137 goals over14 seasons, nor the fact that he was for many years the only black player in the Football League or the first to be appointed a club captain, but as the player who was selected for England and then dropped because of the colour of his skin.

The England FA- an amateur affair

The story of Jack’s selection for England began on the afternoon of Monday 5thOctober 1925 at White Hart Lane, venue of that year’s Charity Shield match. The FA decreed that the Shield that year would be contested between the Amateurs and the Professionals. The Amateurs won comfortably, by six goals to one. This was the first time since 1886 that the Amateurs had defeated the Professionals.

Amongst the crowd of almost 5,000 were the 14 FA Committee members who had selected the Amateurs team. The Professionals comprised players who had taken part in an FA tour of Australia the previous summer.

This was all very convenient as, that very evening, a dinner was being held at Fracati’s in Oxford Street in honour of the touring squad. The FA Committee men and the Professionals were all, of course, invited and no doubt looking forward to the fine food and wine.

The tourists were each to receive a gold medal and what was described as an ‘England international cap’ although the games in Australia did not attract full international status.

Before the Committee members could leave White Hart Lane and get back to their hotels in order to change and head off to the festivities at Fracati’s they had the task of selecting the FA Amateur team to play the RAF and the full England team to take on Northern Ireland later that month.

No doubt impressed and influenced by what they had just observed on the White Hart Lane pitch they selected no less than three members of the Amateurs side. Indeed, Claude Ashton, who scored four goals that day, was named as captain. Quite remarkable for a man who was winning his first and, as it transpired, only cap. Ashton was undoubtedly a fine player but his football was played with the famous Corinthians and he never appeared in a single Football League game in his career.

An all-round sportsman, Ashton also played cricket for Cambridge University and Essex. When he played football for Cambridge University along with his brothers Hubert and Gilbert the team were given the title of ‘Ashton Villa.’ Ashton was killed in a flying accident in 1942 while serving with the RAF.

The other amateurs selected for the England side were goalkeeper Howard Baker of Chelsea and Third Division Charlton Athletic’s centre half, George Armitage.

Baker, another great all-round sportsman, had competed for Great Britain in the high jump and triple jump at the 1912 and 1920 Olympics and was a former team-mate of Ashton’s at Corinthians.

The third of the amateurs chosen that day, George Armitage, would meet a tragic end in August 1936 when he was found dead on a railway line at Aylesford in Kent. He was only 38 years old and had been a patient at the nearby Preston Hall Sanatorium where he was being treated for Tuberculosis.

The Committee ended its deliberations by naming a squad of 13; 11 starters plus two travelling reserves, one of whom was Jack Leslie of Plymouth Argyle. Jack was on the verge of playing for the country of his birth.

But before we go on to look into the circumstances that followed Jack’s selection let us look at who Jack Leslie was.

Jack Leslie-origins

Jack’s father, also John Francis Leslie, was born in Hope Bay, Jamaica on 17th December 1863. John became a mariner and travelled the world. It seems that one route he commonly took was between London and Sydney, Australia. It was while he was in London that he met Anne Regler a young lady from Islington, London. The pair married on 22nd August 1891 and went on to have two daughters Edithe and Letitia Georgina and, on 17th August 1901, a son, Jack Leslie.

We know that John continued going to sea after his marriage. Indeed, he spent his first Christmas and New Year as a married man on the ship “the Salvera” en route from London to Sydney. However, by April 1901 he had settled in 60, Clifton Road, Canning Town with his wife Anne, their two daughters and Anne’s mother. John had found work as a general labourer and Anne, who was pregnant with Jack, worked as a tailoress.

By the time of the 1911 census Jack’s sister, Edithe, had died and the family, including the now 83-year-old mother-in-law Catherine Ann Regler, had moved to 12, Gerald Road, Canning Town. This would remain the family home for many years.

John now described himself as a gas fitter’s labourer, Anne was still a tailoress and 18-year-old Letitia was a dressmaker. The house only had 4 rooms for 5 occupants, so conditions would have been cramped but no doubt Jack spent most of his time outdoors playing football.

After leaving school Jack worked as a boilermaker and joined the United Society of Boilermakers and Iron Shipbuilders Trades Union East Ham Branch on 21st October 1920. It was an occupation he was to return to after his football career was over.

Barking FC

Jack’s first club was London League side, Barking Town. During his time at Barking the club won the Essex Senior Cup in 1919/20 and the Premier Division of the London League and the London Senior Cup the following season.

Still in his teens, Jack was selected to play for Essex on eight occasions and represented both Essex and the London League in international competitions in Paris.

Jack’s prolific scoring record attracted the attention of Plymouth who had entered the newly created Third Division of the Football League in 1920/21 finishing in mid-table. Jack signed for the Pilgrims on 21st June 1921 in advance of the 1921/22 season when a further change had resulted in the creation of Divisions Three North and South. Plymouth, of course, competed in Division Three (South). Barking Town were left rather depleted as, in addition to Jack, Plymouth signed Frank Richardson and Alf Rowe from the non-league side. At least Jack would have company down in Devon.

Jack Leslie at Argyle-the only black footballer in the English league

Jack made his first appearance on 19th November 1921 in a goalless draw at home to Merthyr Tydfil in front of a crowd of 14,000. Jack kept his place in the first team for the next six games until he was dropped after the home derby with Exeter City on 27th December 1921.

Jack was the only black player in the Football League at that time. It would not be until Eddie Parris arrived on the scene in 1929 that he was joined by another blackfootballer. The chances of Jack and Eddie meeting up seemed slim as Eddie’s club, Bradford Park Avenue, were a leading Second Division side at the time.

In a strange quirk of fate Bradford Park Avenue were drawn against Plymouth in the Fourth Round of the FA Cup in January 1929. The press regarded this as quite an event and the headline “Coloured Cup-Tie Rivals,” alongside large photographs of Jack and Eddie was carried by several newspapers. In the event Eddie missed the game so the clash of the two ‘coloured’ players was delayed.

It was 19th December 1931 before Jack and Eddie faced one another on the football pitch, Bradford running out 2-0 winners. Ironically only two weeks earlier Eddie had become Wales’ first black player in a 4-0 defeat in Belfast against Northern Ireland.

Chelsea manager Leslie Knighton’s column in the Daily Mirror of 4th November 1933 reminded readers that there were only “two men of colour” in the Football League – Jack and Eddie. Jack is referred to as “the famous Frank Leslie” and his wing partnership with Plymouth colleague Sam Black was described as “one of the most famous of post-war football.”

Knighton went on to make the prophesy that while “foreigners, Colonials and men from the dominions” add a touch of variety to football he doubts we shall see foreigners imported into the country in the future. Notwithstanding that Jack was born in England and Eddie in Wales, Knighton could not have been more wrong. I wonder what he would think if he walked into the Chelsea dressing room in the modern era when it is not unusual for the entire team to have no home grown players.

As one of the only two black players in the 1920s, Jack did suffer racist abuse both on and off the pitch. He said “I used to get a lot of abuse in matches. “Here darkie, I’m going to break your leg” they’d shout.” Jack chose to regard it as players just trying to get under his skin. Today such comments would lead to a lengthy ban but in the 1920s it was perfectly common to refer to black people as ‘darkie’ or even worse.

Plymouth went from strength to strength during the course of the season and going into the last game at Queens Park Rangers they needed only a single point to guarantee promotion to Division Two. They were top of the League, hadn’t lost in the 16 games they had played since 21st January 1922 and had beaten Queens Park Rangers 4-0 the previous week, what could possibly go wrong? Jack regained his place for this crucial fixture after being out of first team action for over four months. Plymouth lost 2-0 and Southampton, who defeated Newport County 5-0, pipped them on goal average. In those days only the winners of Divisions Three North and South were promoted. Jack ended his first season in the Football League with nine appearances and not a single goal.

The following season was again one of disappointment for Jack. He didn’t make a first team appearance until the First Round of the FA Cup at Notts County on 17th January 1923. Plymouth won 1-0 but again Jack didn’t score, nor did he score threedays later in a 1-1 home draw with Norwich City.

Once again, he lost his place having to wait until 18th April 1923 when he was recalled for a home game against Gillingham. At last Jack broke his scoring duck hitting the second goal in a 2-0 win. This was his 12th appearance for Plymouth and came one day short of 17 months since his debut.

Of the three players Plymouth recruited from Barking in the summer of 1921, Frank Richardson had far the greatest and speediest impact. He could not have got off to a better start scoring a hat trick on his debut, a 3-1 win at Bristol Rovers on 27th August 1921. This was the first ever hat trick scored by a Plymouth player in the Football League. Richardson ended the season with 31 goals from 41 League appearances.

He also became the first Plymouth player to hit a hat trick in the FA Cup when he scored four against Bradford Park Avenue in February 1923. He joined Division One side Stoke City the following month.

Like Jack, Alf Rowe got off to a slow start at Plymouth. Over four seasons from and including 1921/22 he played 41 League games for Argyle without finding the net. He then joined Queens Park Rangers and promptly scored on his debut! But he did have the distinction of scoring the only goal of the game as Plymouth beat Argentina on 13th July 1924 during the club’s tour of South America.

Jack hit a further two goals on 2nd May 1923 in a 3-0 home victory against Brentford. Once again Plymouth ended the season in second place but this time they were six points behind champions Bristol City. In seven appearances in 1922/23 Jack scored three goals.

Bob Jack, a Scot, was the manager who had signed Jack for Plymouth. Bob Jack was a Plymouth legend and as well as playing for them, managed the club for 29 years. It is no wonder his ashes were spread on Plymouth’s Home Park ground when he died. He could be forgiven however, if his mind wasn’t 100% on Plymouth when they played at home to Newport County on 28th April 1923. On that same day, 220 miles or so from Plymouth, Bob’s son the famous David Jack was playing for Bolton in the first ever FA Cup Final to be played at what was then the ‘new’ Wembley Stadium. It became known as the White Horse Final as a policeman on a white horse called Billy struggled to contain the 120,000 crowd that had crammedinto the new stadium.

That day David Jack scored the first ever goal at Wembley after only two minutes as Bolton overcame Second Division West Ham, a club Jack Leslie would one day be employed by. David Jack had previously played for Plymouth, including appearing in their first ever League game, before moving to Bolton. He went on to become the first player in the world to be transferred for a fee of more than £10,000 when he moved from Bolton to Arsenal in 1928. He played for and captained England, scored the only goal in the 1925/26 FA Cup Final when Bolton beat Manchester City and in 1929/30 became the first player to play for two different FA Cup winning sides at Wembley.

Meanwhile Jack Leslie could only dream of Wembley and hope that in 1923/24 he could gain a regular place in the Plymouth team.

It wasn’t to be however. Playing in the inside-left position, Jack scored only two goals in the first 15 games he played that season. Three goals in his last two games bolstered his statistics to five goals in 17 games as Plymouth once again finished runners-up in Division Three (South), four points behind Portsmouth.

At this stage of his career there were few signs that Jack would go on to become a Plymouth legend let alone be chosen for England.

Jack Leslie’s Argyle tour South America

In the Summer of 1924 Plymouth went on a five-week tour of Argentina and Uruguay. That was not however, the first time Jack had travelled abroad as he had played representative football in France while he was with Barking.

The team and officials travelled to South America by boat and played nine games between 22nd June and 20th July beating Argentina twice and Uruguay once. Jack was a regular in the side and scored twice against Uruguay; the first in a 4-0 victory over the South Americans and the second, a late equaliser in a 1-1 draw.

The return journey on the Steam Ship Andes was lengthy and made even longer by stops in Brazil, Uruguay, Portugal and Spain. The players all travelled in Second Class (imagine that happening today!) but manager Bob Jack was housed in the luxury of First Class. There were 226 people on board the ship when it docked at Southampton on 11th August 1924. This was cutting things a bit fine as Argyle’s first League match at Norwich was scheduled for 30th August.

Jack at last became a regular in the Plymouth side in 1924/25 playing in 40 League games and one FA Cup tie. He scored 14 goals including his first ever hat trick in a 7-1 home massacre of Bristol City on 10th April 1925. However, Jack had gone 23 games without a goal prior to the Bristol City game. He needed to start scoring on a more consistent basis.

There were no obvious signs of long-term fatigue from the South American trip as Plymouth played their 42nd and final League match on 29th April 1925 beating Southend 6-0. Jack was on the score sheet. This victory left Plymouth at the top of the League, three points ahead of Swansea who had two games remaining. Plymouth had a superior goal average so Swansea had to win both their remaining games to pip Argyle to the title and promotion to Division Two.

The following day Swansea scraped a 1-0 win at home to Reading, the winner coming late in the game.

Everything rested on the Swansea’s final game of the season two days after the Reading game, at home to Plymouth’s Devon rivals Exeter City. The Grecians had nothing to play for but could they do their neighbours a favour? Swansea raced into a two-goal lead by half-time their first goal coming from former Argyle centre-forward Jack Fowler who had made his Plymouth debut just one month after Jack played his first game for the club. Exeter pulled one back in the second half but couldn’t snatch an equaliser. Swansea were promoted and Plymouth for the fourth season in succession finished runners-up.

In many ways the crunch clash had been Plymouth’s penultimate game of the season on 25th April 1925, when a crowd of 30,000 saw Argyle draw 1-1 at home to their promotion rivals Swansea. A win for Plymouth would have seen them take the title.

Jack returned to London in the close season to marry East-London girl Lavinia Emma Garland on 27th June 1925. The couple had a daughter, Evelyn, in 1927 and settled in Glendower Road, Plymouth.

While at Plymouth Jack earned only £8 a week during the football season and £6 a week in the close season. There was a bonus of £2 for a win and £1 for a draw. Fortunately for Jack and his team mates, Plymouth won more games than they lost.

Jack’s family

While Jack’s childhood was not a bed of roses, Lavinia had an even tougher upbringing. Born on 21st November 1899 (although she was not baptised until 3rdNovember 1907) in 1901 she was living at 25, Welstead Road, East Ham along with her father William Alfred and mother Emma plus the couple’s six children; Florence Edith (born 1888-died 1944); William Edward Rockliffe (born 2nd June 1891-died 1957); Sarah Ann (born 20th February 1893-died 23rd October 1950); Frances Lydia (born 20th March 1895-died 1976); Annie (born 14th June 1897-died 1978) and finally baby Lavinia.

William senior was born in Gravesend and Emma hailed from Bedfordshire. The saddest entry on the 1901 census is the description of Lavinia’s father as a ‘lunatic.’ This is a term repeated on the 1911 census yet only four years later William was cleared as fit to serve in World War 1. It appears, judging from the 1891 census, that far from being a ‘lunatic’ William was simply deaf.

The Garland family were living at 198, Queen’s Road, Plaistow in 1911. William senior and his son William junior although both recorded as general labourers wereout of work.

Eleven people were living in the house which had only five rooms. Sarah, now 18 was working as a laundress and Frances was a duty girl. Annie and Lavinia wereboth still at school and the family has been supplemented by two sons -Thomas (born 24th July 1902-died 29th July 1937) and Richard Alfred Rockliffe (born 14thOctober 1907-died 1953).

Making up the 11 inhabitants were Albert and Edward Cross both in their 20s and brothers of Emma. Albert was an unemployed general labourer and Edward a coal hawker.

William states very clearly on the 1911 census form that he and Emma had eight children all of whom were still living. He seems to have overlooked Maud Lily (born 25th June 1904-died 6th October 1958).Maud wasn’t living with her parents when the 1911 census was completed but she is cited, a few years later, as a dependent child on William’s Army records. Maud was in fact living at 34, Landsdown Road, Tidal Basin with her aunt, Annie Maria Cross.

Despite the poverty, poor conditions and overcrowding, all nine of William and Emma’s children survived childhood.

Remarkably, given his age and classification as a lunatic, William senior enlisted in the Army on 13th April 1915 and served in France with the Army Service Corps for a year before being medically discharged. He was 43 years of age at a time when the upper age limit for new recruits was 41. Recruiting officers often accepted people who, strictly speaking, should not have been taken on, such was the desperation to get men out onto the Western Front. We learn from his attestation form that William was a diminutive figure standing 5 feet 2 and three-quarter inches tall. He had a fresh complexion, blue eyes and brown hair.

William sailed for Le Havre from Southampton on 24th September 1915. He was very quickly in trouble with the authorities as on 24th October he was punished because of ‘drunkenness on active service.’

As might have been anticipated, William was not suited to the rigours of War and he was discharged as medically unfit on 9th August 1916. His character was described as ‘good.’ This is perhaps surprising given that in addition to his drunken escapade in October 1915, in June 1916 he was deprived of seven days’ pay for being absent from roll call.

His attestation papers show his address as 111, Queen’s Road, Plaistow, having previously lived at number 198. It wasn’t unusual for families to remain in the same area and move only very short distances when they changed homes. As of August 1916 he had three dependent children.

Strangely William’s medical records show that his discharge was due to ‘indigestion.’ The Army Medical Board noted that William had suffered from this since 1901 and it was neither caused nor aggravated by his military service. This of course meant William would not get a disability pension or gratuity as he returned to East London with its poor employment prospects, overcrowding and abject poverty.

One wonders if William enlisted because of patriotism or simply the lack of employment at that time. Perhaps he felt by leaving home there would be one less mouth for his wife Emma to feed? We shall never know.

William junior also served in and survived World War 1 but was clearly not a man with a great deal of respect for authority. His Army records show a whole list of transgressions; not complying with orders (he had dirty boots on parade); neglect of duty; absent for adjutant’s parade; gambling in a tent; not complying with an officer’s orders; absence from parade; and finally, two offences of absence without leave. Despite this his military character was assessed as ‘fair’ and his general character ‘good.’

After marrying Jack, Lavinia must have found the peace and quiet of Plymouth a total change from the hustle and bustle of East London. One hopes she quickly adapted to married life and savoured the changes to her living conditions. It certainly seemed to be a happy marriage and the couple remained together for almost 63 years until Lavinia’s death in 1988.

Jack had left London in the summer of 1921 and it is presumed he had met Lavinia before leaving the East End. Quite why the pair waited four years before marrying is not known. There is however, evidence that Jack spent time in London even after his transfer to Plymouth and he almost certainly returned to London every summer during the close season. Although that would not be the case in 1924 when he spent a large chunk of the summer in South America.

When Jack returned from South America the passenger list for the Andes records his address as the Leslie family’s home at 12, Gerald Road, Canning Town. The majority of the other team members showed addresses in Plymouth. Alf Rowe lived at 94, Trelawney Road and Frank Sloan and Patrick Corcoran lodged together at 34, Onslow Road. Manager Bob Jack’s home at that time was at 146, Peverell Park Road in Plymouth.

1925- Jack hit’s peak form

Plymouth started the 1925/26 season like a house on fire winning ten of their first 12 games, scoring 44 goals in the process. Married life obviously suited Jack who scored eight of those goals. However, he scored only a further nine in the next 29 games.

This avalanche of goals was probably aided by a change to the offside rule in 1925/26. Only two, rather than three, players were now required to be between the attacking player and the goal. This resulted in almost 30% more goals being scored in the Football League compared to the previous season.

As of 9th November 1925, Plymouth had three of the top nine goal scorers in Division Three (South). Jack Cock topped the list with 15, Sammy Black had ten, closely followed by Jack with nine goals.

The England selection committee look at Jack

However, rewinding a little, when the FA Committee met after the Charity Shield on 5th October they perhaps unfurled their newspapers and turned to the sports section to see which clubs were doing well and who their best players were.

They were obviously conscious that the leading sides would not release players for a mid-season international – no international breaks in those days. They were forced to turn to players from the lower divisions and certainly selecting three of the Amateurs team that had performed that day was a good start in filling the 13 places that were available for the upcoming match in Belfast.

Turning to Division Three (South) they will have seen Plymouth Argyle riding high in the League. Their record was an almost perfect one – played 8 won 7 lost one. They had scored 31 goals and conceded only nine. They stood top of the League ahead of Reading on goal average but already with two games in hand of the Berkshire club.

They had won their first two games of the season by six goals to two against Southend and Crystal Palace. In September they went one better and beat Aberdare Athletic 7-2. The previous week they had hammered Brentford by four goals to nil.

Jack had played a leading role and scored six goals so far that season. The selectors perhaps considered the merits of Jack Cock and Sammy Black but it was Jack they picked for the squad naming him as travelling reserve.

We will probably never know just how much time the Committee spent in considering the squad. Perhaps they were overly keen to get off to Oxford Street and begin the evening’s celebrations? Whatever, Jack was in the squad and the details were passed to the Press Association.

Jack Leslie selected for England!

The following day manager Bob Jack called Jack into his office to tell him he’d been picked for England. Whether Bob Jack specified that Jack was named as travelling reserve is almost irrelevant – Jack Leslie of Plymouth Argyle had been picked for England!

The local and national press that day carried the story of the England squad. All showed Jack as travelling reserve.

The Western Morning News of 6th October 1925 was one of many newspapers that published the squad, proudly headlining it with “Argyle Player Reserve Against Ireland.”

There was some muted press criticism of the team the selectors had chosen. The choice of three amateur players was questioned in some quarters and ‘Argus Junior’ writing in the Sports Argus of 10th October 1925 pretty much summed things up when he said “I hope England’s eleven will be more convincing on the field than they are on paper.” Argus’ only direct criticism was aimed at the choice of goalkeeper and half backs. Jack’s place in the squad would appear to have been accepted without attracting comment.

Yet when the squad travelled to the Slieve Donard Hotel in Newcastle, County Down on Wednesday 21st October Jack was not with them. His place as travelling reserve had been taken by Stan Earle of West Ham United. The first indication we can find of Earle replacing Jack is in an article in the Athletic News dated 19th October. Jack’s name is simply replaced by that of Earle – no explanation is offered.

Why was Jack “de-selected” for England?

Jack was not injured or suspended. Indeed he played at Home Park on the day of the international, scoring twice as Plymouth hammered Bournemouth 7-2, while England laboured to a goalless draw in Belfast. The only logical conclusion was that Jack had been dropped because he was black. The question is, did the selectors suddenly discover Jack was black and change their minds or were they perhaps overruled by a superior body?

There is no disputing that Plymouth is geographically remote in terms of League football. Given that football at Third Division level was regionalised it is perfectly possible that the majority of the FA Committee members may never have seen Jack or Plymouth Argyle play.

The 14 were Charles Wreford-Brown (Oxford University), S R B Cowles (Norfolk), Arthur Joshua Dickinson (Sheffield Wednesday), B A Glandell (Amateur Association), Henry J Huband (London FA), Harry Keys (West Bromwich Albion), Arthur Kingscott (Derbyshire FA), John Lewis (Lancashire FA), John McKenna (Liverpool FC), H A Porter (Kent County FA), George Wagstaffe Simmons (Hertfordshire FA), James Alfred Tayler (Gloucestershire FA), Tom Thorne (Millwall FC) and Harry Walker (North Riding County FA).

Wreford-Brown had played for and captained England as an amateur. He was also a talented cricketer having played for Gloucestershire. He had been on the council of the FA since 1892. He was born in Bristol and still had family there. Indeed his cousin Richard Wreford-Brown had shot and killed his father-in-law (an inhabitant of Bristol) in Ross-on-Wye on 14th August 1925. On 5th November 1925 Wreford-Brown was found guilty of murder but regarded as insane so as not to be responsible for his actions.

Of all the selectors Charles Wreford-Brown seems one of the most likely to have been familiar with Jack and, of course, the colour of his skin.

However, it seems inconceivable that the Gloucestershire FA representative cannot have seen Jack play. J A Tayler had been elected President of the Gloucestershire FA in 1899 so definitely no ‘new kid on the block.’ Moreover he was President of the Western League, a competition which covered the entire south-west of England. Indeed the League had been won by Plymouth Argyle in 1905 a feat that would be repeated by Argyle’s reserve side in 1928 and 1932. Surely when Jack began to be discussed by the Committee on the early evening of 5th October the other 13 Committee members would turn to Mr Tayler for his thoughts on the Devon-based footballer?

We also know that the previous summer Bert Batten of Plymouth had been selected for the FA tour of Australia. He missed the Charity Shield game because of injury but would have been invited to the celebrations in London as he had a very successful tour, scoring 47 goals. That might seem like an unbelievable amount of goals but the team scored 139 goals in 25 matches and conceded only 13. Bert scored six goals in a single game – a 10-0 victory against South Australia.

Selection for the tour was very much a double-edged sword. It was a great honour and quite an adventure, but it did suggest that your club was happy for you to exhaust yourself making the arduous journey to and from Australia and playing football from May until August when the English season resumed. Clubs would not allow their most valuable players to take on such a burden.

In the 1923/24 season leading up to his selection, Batten had scored ten goals in 17 League games for Plymouth. Jack was only marginally more prolific with 14 goals but he was very much a mainstay of the team making 40 appearances. One can only conjecture why Jack wasn’t included in the FA party but it is reasonable to suppose that, even if approached, Plymouth would have argued that they needed to keep their star forward fit for the season ahead. One might also presume that if the FA selectors had watched Batten prior to picking him for the tour, they must have seen Jack play and be aware that he was black.

Fine player though Batten was there is plenty of evidence that he was very much in the shadow of Jack. His preferred position was inside left but Jack had made that position his own forcing Batten out wide to play on the left wing.

The second question that doubters raise is ‘was Jack, as a Third Division player, good enough?’ We have already seen that three of the team were amateurs, one of whom never played a single League game in his career. One of the amateurs, George Armitage played for Charlton Athletic who would end the season second from bottom of Division Three (South) and be forced to apply for re-election.

At the time of Jack’s selection he was in his fifth season of League football and had played almost 100 games for Plymouth who were a top notch Division Three (South) side who had only missed out on promotion by the slimmest of margins in the previous four seasons.

Nor did his selection raise any eye brows at the time. The Westminster Gazette of 7thOctober simply remarked that his selection was “interesting.” This is more likely to relate to his footballing ability than the colour of his skin. The Gazette also referred to Jack as “a man of colour.” If a London newspaper journalist knew that Jack was black, surely at least one of the 14 Committee members must also have known? And if they didn’t know they would do after reading the Westminster Gazette! There was no reason to, as claimed, have one or more of the Committee go to Plymouth’s next game to check on his skin colour.

Returning to the question of was Jack good enough, of the team that would take the field in Belfast on 24th October, five players were making their debut, four of whom would never play internationally again. Of the starting 11 no fewer than seven never played for England again and two only played once more. Billy Walker of Aston Villa was far and away the star player going on to play for England 18 times, scoring nine goals. None of the other ten players got into double figures in terms of international caps. In short, apart perhaps from Walker, Jack was at least the equal of every member of that, albeit weakened, England squad.

On the morning of the match, the Northern Whig of 24th October 1925 in providing a pen picture of each member of the squad and totally oblivious of the fact that Jack had been discarded, noted that Jack was a non-playing reserve but said “Leslie who has scored plenty of goals for the Argyle, is an inside forward of great ability and will soon work his way into representative matches.”

There is no evidence whatsoever that Jack was not good enough to represent the country of his birth.

So, the story is true. Jack was selected then dropped and we can think of no other reason than it was due to the colour of his skin. The Daily Herald of 28th October 1925 quoted a letter sent by a ‘London reader’ which asked why Jack had been announced in the squad but Earle of West Ham travelled instead? He went on to plead “Cannot you, in the columns of Labour’s only daily newspaper make a stand against the snobbery which is like a blight on first class football.” He added that it was nonsensical that Ashton of the Corinthians had been named as captain when he patently was not an international class footballer.

There is just a hint here that the reason for Jack’s exclusion was linked to class and perhaps the assumption that a black man must come from a very low class?

The Herald took the matter up with the FA who in a stubborn and illogical stance, denied that Jack had ever been chosen! An early example of fake news perhaps? The Herald then took the matter up with the Press Association, who, if the FA was telling the truth, had misreported Jack’s selection. The Press Association was adamant the FA had indeed announced Jack as a travelling reserve.

I think we have established beyond any doubt that Jack was indeed selected for England on the afternoon of 5th October and also that he was in the squad on merit. What is beyond dispute is that he was not invited to join the England squad that left for Belfast later that month.

Is it really conceivable that Jack was quietly dropped because of the colour of his skin? Was Jack really selected by 14 Committee members none of whom knew he was black, even though the Westminster Gazette, for example, readily recognised him as “a man of colour.”

As we have noted, Jack had played almost 100 League games over five seasons. It is unthinkable that not one of those games had been observed by an FA Committee member.

We might never know what was discussed at that selection meeting at White Hart Lane on 5th October 1925 but surely someone must have spoken for Jack and put a case forward for his selection? If that was the case one can only suppose Jack’s benefactor(s) did not mention the colour of his skin, perhaps thinking it irrelevant. Nor could we expect the other Committee members to ask whether Jack was white. It was simply a question that did not arise, after all every player in the entire Football League was white…apart from Jack.

Is it really conceivable that a country’s football squad could be chosen by people who had not seen the individual players in action?

One school of thought is that one or more of the selectors went to watch Jack play between 5th October (the date of the selection Committee meeting) and 19th October, when the Athletic News quoted Stan Earle and Harry Nuttall as the travelling reserves and that it was while watching Jack that they became aware that he was black.

The FA Council met on 19th October 1925 at Russell Square. When the England team for Northern Ireland was discussed it was to check on the fitness of Notts County full-back Horace Cope of Notts County and confirm that Nuttall who was named as a travelling reserve was unfit and his place would be taken by Alf Baker of Arsenal. Unlucky Cope was ruled out through injury and never won an England cap. His place was taken by Frank Hudspeth of Newcastle who aged 35 years 6 months and four days won his first and only cap. Baker went on to make a solitary England appearance in 1927. No mention is made of Jack.

Plymouth played two games over this period; at home to Watford (a 2-1 victory) on 10th October and away to Reading the following Saturday in a top of the table battle that ended in a 1-1 draw.

This requires us to accept the bizarre theory that England had originally chosen a squad member without ever having seen him play. And why, having chosen the squad, would the selectors then want to take another look at the players they had selected? Did they carry out this ‘check’ on all 13 members of the squad? And if so, why was Jack the only player to then be ‘de-selected?’ The only thing different about Jack was, of course, the colour of his skin.

It seems unlikely the FA would send a Committee member all the way to Devon simply to check on Jack so, if this theory has any credence, Jack’s dark-skin was ‘discovered’ at Reading only a week before the Northern Ireland game and he was dropped that weekend as his name no longer appeared as travelling reserve in an article in the Athletic News the following Monday.

FACT: The FA dropped Jack Leslie because he was black

The facts are that Jack was selected for England on 5th October but by the time of the game he had been quietly de-selected. The only reason can be the colour of his skin. What changed between 5th and 19th October when his name disappeared from the squad? We don’t know what degree of consideration the FA Committee put in to selecting the 13-man squad but they selected Jack and were confident enough in their choice to hand the squad names to the Press Association. It seems highly unlikely they could be unaware of Jack’s heritage. So, were they over-ruled by an external body?

The FA President Charles Clegg was at White Hart Lane when the selection Committee met so the squad effectively had the seal of approval of the most senior official in the FA. Clegg was a deeply religious and devout man but liberal minded. He was a straight talking northerner and a solicitor who didn’t always get along with some, what he considered ‘snobby’ solicitors from the south.

All of this raises the question of whether the FA was told by another body to quietly drop Jack from the squad. But who was more powerful and influential than the FA? The Government perhaps? The recently elected Conservative Government under the leadership of Stanley Baldwin may have had in mind the 1919 Race Riots which took place in ports across the country where white men fought in protest against the perception that black men had taken their jobs and, in some cases, their women, while they were away fighting in the Great War.

Jack was never named in an England squad again despite hitting even higher levels of form later in his career.

This must rank as one of the most shameful incidents in the long and far from blemish-free history of the FA. We may never know the truth. There are a number of possible scenarios the most unlikely of which by a distance is that put forward by the FA that they never selected Jack at any point despite what the Press Association was told.

Jack expressed no bitterness. His version of events was that he “did hear, roundabout like, that the FA had come to have another look at me. Not at me football but at me face. They asked and found they’d made a ricket. Found out about me daddy and that was it.”

“There was a bit of an uproar in the papers. Folks in the town were very upset. No one ever told me official like but that had to be the reason; me mum was English but me daddy was black as the ace of spades. There wasn’t any other reason for taking my cap away.”

What is strange is that, despite what Jack said, there seems to have been no comment in the press. Was the news and the reasons for Jack’s exclusion supressed? Certainly one local reporter claimed his “pen is under a ban in this matter.” What sort of body had such a hold over the press?

Apart from the ill-informed article in the Northern Whig on the morning of the Ireland match, the only known reference to Jack after 6th October is in the Western Daily Press on 12th October 1925 where it is suggested that “Leslie, the darkie forward of Plymouth Argyle” was likely to take the place of Sam Wadsworth of Huddersfield in the England team. Wadsworth had been named in the original starting eleven. This seems a remarkably ill-advised claim as Wadsworth was a full-back, a position Jack had never filled. But note that the Northern Whig was another paper that, albeit somewhat disrespectfully, recognised Jack as non-white. If they knew, then surely the selectors must also have known.

The press followed and reported on the battles Cope and Nuttall were having to get fit for the match. The latter was a ‘mere’ reserve, just like Jack. Yet Jack disappeared from the squad and his omission attracted no press coverage.

Jack’s continuing success at Plymouth Argyle

But life went on and Plymouth continued to ride high in the League table vying with Reading for the coveted promotion slot.

On 24th April 1926 the Jack family had plenty to celebrate. David Jack had just scored the only goal of the game to win the FA Cup for Arsenal and dad Bob Jack had watched his Plymouth team beat Charlton at home by 1-0 while arch promotion rivals Reading had lost 3-0 at Crystal Palace. Plymouth stood top of the League on goal average ahead of Reading. Plymouth had two games to play whereas Reading only had one to go. Surely nothing would go wrong this time?

On Monday 26th April 1926 Plymouth played their game in hand and got a point in a 2-2 draw at Brentford. The last games of the season on 2nd May 1926 saw Plymouth travel to Gillingham and Reading host Brentford. A point would probably be enough to see Plymouth take the title but they succumbed 2-0 to Gillingham while Reading hammered Brentford 7-1. Yet again, Plymouth were runners-up.

The following season Plymouth abandoned their habit of finishing the season badly and won their last six games only to finish second again, two points behind Bristol City who they had beaten 4-2 in the penultimate game of the season. In 33 League games and one FA Cup game Jack scored 14 goals including the second hat trick of his career in a 7-1 home victory over Crystal Palace on 12th February 1927.

There was to be no near miss for Plymouth in 1927/28 as they slipped to third place,12 points behind champions Millwall. Jack scored 15 goals in 41 League games and didn’t score in his only FA Cup appearance.

The highlight of the 1928/29 season was a 3-0 Third Round FA Cup victory over Division Two side Blackpool thanks to a Sammy Black hat trick. Black and Jack formed a renowned left-wing partnership for Plymouth over several seasons playing together 327 times.

Plymouth were knocked out at home to Bradford Park Avenue in the next round on 26th January 1929. This was the game the Leeds Mercury of 25th January 1929 tagged “Coloured Cup Tie Rivals” and under large photographs of Jack and Eddie Parris of Bradford commented “Bradford and Plymouth meet in tomorrow’s cup ties. Each club possesses a coloured player.” As stated earlier Eddie Parris did not play in this game.

Plymouth didn’t win any of the next eight League games after beating Blackpool. A late surge, winning each of their last four League games, only took them from eighthto fourth place although a mere two points behind champions Charlton. Jack had his best season so far and scored 22 goals in 41 League games as well as scoring once in four FA Cup ties.

Promotion– and Jack Leslie as club captain!

Plymouth finally clinched the title in 1929/30 winning the League by seven points after amassing what was then a record for Division Three (South) of 68 points. They lost only four League games all season.

Jack had a relatively disappointing season. He scored eight goals in 32 League games and once in four FA Cup matches but didn’t find the net in any of his last 14 games. Plymouth scored 98 League goals and Jack was only their fifth highest scorer.

Plymouth played their first ever Division Two game at home to Everton on 30th August 1930. Everton had just been relegated and were to win the League that season by seven points. Jack had a good start scoring in a 3-2 loss in front of a bumper crowd of 34,236. Plymouth lost the return game to Everton 9-1 in December 1929 with the great Dixie Dean scoring four of the goals. Dean scored 48 League and Cup goals that season but nowhere near the 63 he scored in 1927/28!

Plymouth finished the season in 18th place six points clear of relegation. Jack scored eight goals in 39 League and FA Cup appearances making him the club’s fourth top scorer that season.

1931/32 was Jack and Plymouth’s best season to date. Plymouth finished fourth in Division Two and Jack, who was now club captain, scored 21 goals in 43 League and FA Cup games. This included a hat trick in a 3-3 home draw with Bradford City on 12th September 1931 and four goals in a 5-1 home rout of Nottingham Forest on 17th October 1931.

The significance of Jack being appointed club captain should not be under estimated. He was certainly the first black footballer to achieve that feat in the Football League, it would be 1969 before another such occurrence when Stan Horne was made captain of Fulham. Put bluntly white people were not used to taking orders from black men, there was also a perception amongst some, that black people were not natural leaders.

Jack flying high

Jack’s status as captain did result in him making his first journey by air. In October 1932 Plymouth experimented with flying to away games. The first such venture was a trip to Stoke. The journey took only just over two hours by air compared to over ten hours by rail. Players were excluded from the outward journey which was limited to club officials and their friends. As captain, Jack was the only player allowed to join the return flight which included Bob Jack, his wife and their 31-year-old son Rollo. It was Jack’s first flight as it was for Mr and Mrs Jack.

Sadly, Jack now in his 30s, never again showed the form he had in 1931/32. The following season he scored only five times in 33 appearances as Plymouth finished 14th in Division Two.

His last two seasons were blighted by an injury he suffered when the lace on a ball went into his eye. He played 11 games in 1933/34 before the injury, which took place at Lincoln during a 1-1 draw. The damage was so serious it was thought he would not play again.

When Plymouth announced their list of retained players at the end of the 1933/34 season Jack’s name was absent. Showing no sentiment whatsoever the club were unwilling to offer Jack a further contract until it could be shown that he had fully recovered from the injury that was now affecting both eyes. This must have been an incredibly worrying time for Jack and Lavinia not only in respect to the danger to his sight but also financially. Jack was in his early 30s, nearing the end of his football career and daughter Evelyn had recently started going to school in Plymouth.

Fortunately Plymouth rather belatedly offered him a new contract in June 1934 when the specialist treating him gave an optimistic report about his recovery.

1933/34 was also Jack’s benefit year and at the end of the season he was presented in person with a cheque for 10 guineas on behalf of the club at the annual supper and social of the grandly named Ladies Auxiliary Committee of the Plymouth Argyle Supporters’ Club.

Jack never regained his previous form and played only once in 1934/35. His last game was on 29th December 1934 when, wearing the number nine shirt, he scored the first goal in a 3-1 victory at home to Fulham. He was given a free transfer at the end of the season.

Retirement-and return to London

Jack and Lavinia moved to Truro where they ran a pub. Jack even played a few games at centre half for Truro in the Plymouth and District League. By 1938 the Leslie family had returned to London and were living at 132, Wakefield Street, East Ham not far from Jack’s father who by then was a widower. Jack returned to his employment of boilermaker and Lavinia worked as a cardboard box maker.

John Francis senior was still living at the old family home at 12, Gerald Road in Canning Town. With him was Jack’s sister Letitia and her second husband George Gillick and the couple’s children. Also in the household were Letitia’s children from her first marriage to Walter Henry Oxley who died age 43 on 4th August 1934.

In August 1938 Jack was appointed as Barking Town FC’s trainer. In reporting this, the Western News of 4th August 1938 described Jack as “one of the finest players ever to wear an Argyle jersey. He played at inside-left and was a tactician of outstanding quality.”

West Ham

Jack also worked as boot-boy for West Ham until he was 80 years of age. His retirement was celebrated on London Weekend Television’s ‘The Big Match’ which showed West Ham manager John Lyall giving a speech and thanking Jack for all his service.

Final Years

Jack and Lavinia lived their later years in Gravesend where Lavinia died on 10th April 1988 followed seven months later on 25th November by Jack at the age of 88. Jack’s death certificate shows him not as an ex-professional footballer but rather a “retired boilermaker.” He was a modest, unassuming man right up to the very end.

Bill Hern, December 2020

NOTES (Greg Foxsmith)

1 I am very grateful to Bill, for this article and allowing me to publish it on this site, and for the extensive research that underpins this endeavour. When I first corresponded with Bill, the Jack Leslie Campaign had launched (we had a website and twitter account) but the crowdfunder appeal had not, and his book (jointly written with David Gleave) had not yet gone to print. Bill was generous with his time and in sharing his research as we all learned more about Jack Leslie. He has become a friend, and I look forward to meeting him in person when circumstances allow.

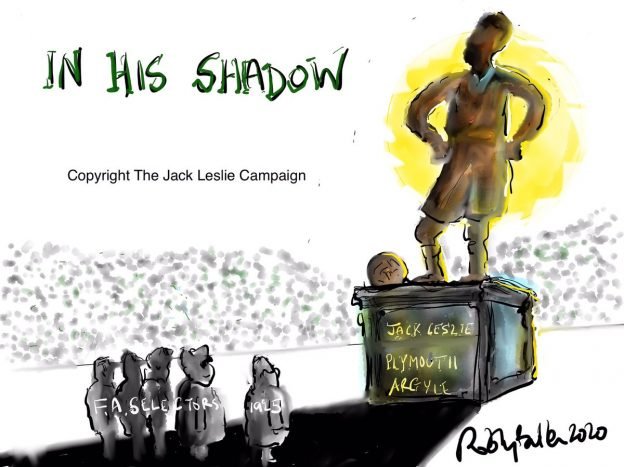

2 “In 2020 two Argyle fans launched the JACK LESLIE CAMPAIGN,….” those two fans were myself and Matt Tiller, and like Bill we had only vague knowledge of Jack Leslie (and none of the England selection story) until a year ago. Matt’s journey of enlightenment is recounted here, and mine on an earlier blog here. The catalyst for all this was Matt meeting Tony, who became one of the Campaign Committee along with these great people (one of whom, cartoonist Rob Bullen, created the lead illustration for this blog)

3 Buy Bill and David’s book here: https://www.conkereditions.co.uk/product/footballs-black-pioneers-subscriber-copies-for-pre-order/

4 Support the Jack Leslie Campaign! https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/jack-leslie-campaign

5 About the author- Bill Hern is a life-long supporter of Sunderland FC. He is on twitter as @HernBill

6 COPYRIGHT- this article was researched and written by Bill, who retains copyright and IP rights over this material. That said, he is usually very amenable to agreeing reproduction of his work if properly credited to him, so do go ahead and give him a shout if you would like to publish all or some of this article, and he is very likely to grant permission.